Collaboration at the Digital Society School.

Dit artikel is hier in het Nederlands te lezen.

I am very upset. Not for me but for the others that were waiting for us

Thus spoke the one student who showed up on time for my appointment with four students and a coach from the Digital Society School on November 28. At DSS, students collaborate on projects in multidisciplinary and multicultural teams. I wanted them to try out the Collaboration-themed card set that I’d previously used at the minor Design Thinking and Doing. During the workshop I witnessed, more than ever before, how potentially difficult collaboration can be and how positive the effects of discussing it in a controlled environment could be.

Digital Society School

The Digital Society School is a learning community within the Amsterdam AUAS where students follow an internship, during which they research technology’s impact on modern society and develop skills that will help them shape today’s digital world.

Tracks

In DSS, students work in teams on several different projects, which are called tracks. They work on these tracks in sprints. Each sprint culminates in an evaluation. I decided to apply my method as an evaluation tool at the end of these students’ third sprint.

Data Driven Transformation

The students in my workshop are on the Data Driven Transformation track. In this project, they’re researching how new climate movements (founded after 2017) are communicating and are being represented by media. The students are creating datasets by collecting data on social media – like Facebook hashtags – to design an interactive installation that showcases patterns within these datasets.

Multicultural and multidisciplinary teams

The Digital Society School is an attractive opportunity for foreign students looking to land a job in The Netherlands. They will get a temporary visa during the course and if they do find a job, they will be able to stay in the country on a work visa. This means the DSS encompasses students of many different origins and cultures. The students participating in my workshop were from Chili, India, the US and Italy. They studied software engineering, visual/frontend design, social work and international business & management and (almost) all of them received their master’s degree.

Setting

In the end, there were five participants:

Cristiano, coach, from Italy

Roman, also from Italy

Salina from India

Diego from Greece

Walter from the USA

Cristiano, the coach, decided to participate in the workshop himself. He and I selected a few themes from the same card set that I used during the Design Thinking workshop. During the workshop, we communicated in English which led to a few misunderstandings, even if the students knew the language well. Not every student was thrilled with the idea of having to draw, but in the end all of them participated at least partly.

Too late

Three of the students were at least fifteen minutes late. One of the team members didn’t show up at all. Cristiano and Roman did show up on time. Roman drew the Responsibility and Where cards. He drew a picture of a calendar and a clock and said:

For me it was very easy. I drew an agenda and a clock. You need to respect the time of others. You could have the greatest idea or be the biggest genius in the world. If you are not on time, you can’t sit at the table of decisions others make.

The other students were laughing uncomfortably. Salina called out:

Too much anger, too much anger.

Their coach responded:

I actually drew something similar, my cards said Professional and What. For you in the the future, if you want to apply for a job, keep in mind: we all come from a different cultural setting so the concept of time can vary but the concept of agreement is something you should stick with to be more professional. As a group, if you agree on something you should stick with these simple rules.

Walter responded by saying:

Maybe if we agreed on the time, we could have all been here on time, but we didn’t have any input, you know’. It was just decided, you know.

Coach:

So it was not clear to you that we started at ten?

Walter:

Yes it was, but we were told yesterday, and of course that is enough notice, but we are now talking that we should all agree on it and I didn’t agree on it.

To which Salina said:

I was there on time but I couldn’t open Slack on my phone so I didn’t know the location.

Coach:

So in the future I should give you more notice on what we agree on?

Roman:

I think it is the basic of our collaboration. We know we have tools like Slack that we have to check.

Salina:

But it’s not working on my phone, I did try it out and eventually switched it on on my laptop.

Roman:

Of course it is clear and none of it is personal. Now I can say ‘ok’ but another person could say, it’s not my problem if you don’t check Slack. Everyone has to check Slack.

Salina:

It’s on your phone, it’s not on my phone.

Roman:

I understand but you have to understand me.

Diego:

We start the conversation with lame excuses, we have to be here on time. That’s it. Why are we talking about this?

Coach:

Is this an issue that happened before?

Walter:

For me it is not an issue, you know. I don’t care when you come in or when you leave. As long as you do your job. I’m flexible.

Coach:

I understand but maybe other people think differently about this. Maybe you can use this to talk about a new agreement? Take your time to think about it and maybe you can decide in the next couple of days.

Roman:

It worked before and you don’t have to come on time every day but as a team we should be capable of coming on time.

Walter:

To defend myself, this never happened before. And the tv didn’t even work when we got here. So it wasn’t actually a problem at all.

Roman:

You can keep saying these things but it’s not about that.

Coach:

Ok, let’s try another round.

The conversation above demonstrates how a simple subject like arriving on time can be a topic of discussion and lead to aggravation and miscommunication. I’ll be devoting more attention to dialogue from this session in my next post. For now: it seems like the method’s clear-cut rules made sure the coach was able to have everyone have their say. They also allowed him to halt the conversation by moving on to the next round.

It is important that the coach stick to the allotted time limits – in this case, two minutes to draw and five minutes to share everyone’s drawings and the ensuing conversation.

In general

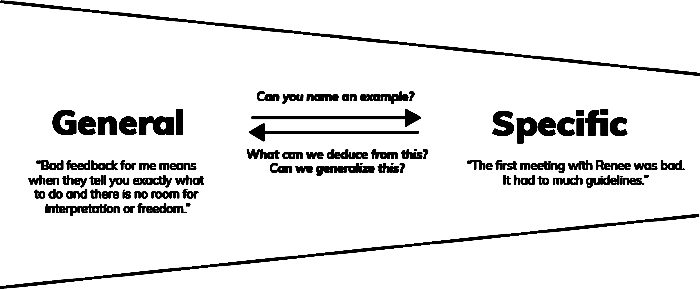

The point of my method is that participants will dive in deeper into subjects when they’re drawing than when they’re writing or talking about them. When Love is theme, it’s easy (and commonplace) to draw a heart. When Love is theme combined with Where, a participant will have to come up with something more specific.

Using personal themes, like I did when trying the method with a group of friends, children and their parents, mental healthcare and a family, the method tends to work well. The themes that I’m currently workshopping at the AUAS – Collaboration and The designer’s role – are hit and miss. I’m not yet convinced whether this is primarily an issue with the participants’ personalities or the themes within the game. When I used the theme of Collaboration in the minor Design Thinking workshop, students would rarely dip below the surface, but they were able to relate certain tropes to what they were doing – which is to say, collaborating.

During the DDS session, Salina, who drew the Bad project and Where cards, noted that a general concept like ‘a bad project’ does not exist and that it’s always dependent on context and the experience and vision of the person involved.

I’m also interested in the individual’s point of view and I do hope that participants will interpret their themes this way or are able to relate to the broadly defined terms in a personal way, and thus give examples of (and possibly draw conclusions based on) personal experiences when confronted with these terms.

This is something that they sometimes fail to do now, which could be due to the phrasing I’ve used in the themes. For example, Bad project may be better phrased as My worst project. Then again, a person doesn’t necessarily need to have actually experienced something themselves – it could also be something they saw happen near them, for example to friends or classmates.

The coach did follow up on asking Salina about her bad project, but he didn’t get a clear answer. Walter took issue with the themes that incorporated the word ‘bad’, because he felt the phrasing was too negative. During my try-out with the students from the Design Thinking minor, none of the participants voiced similar issues. Still, I’ll be considering rephrasing the theme keywords.

The conversation that arose after the negatively worded theme cards did prove fruitful: the participants ended up establishing a clear set of ‘rules’, like being more transparent and open, that could help improve their collaboration. After an interesting, if slightly awkward discussion about the concept of rules versus liberty (“So you don’t like freedom?”), the conversation around the theme of Bad feedback led to the conclusion that some students need guidance and structure more than others. That is useful information to a collaborating group like this.

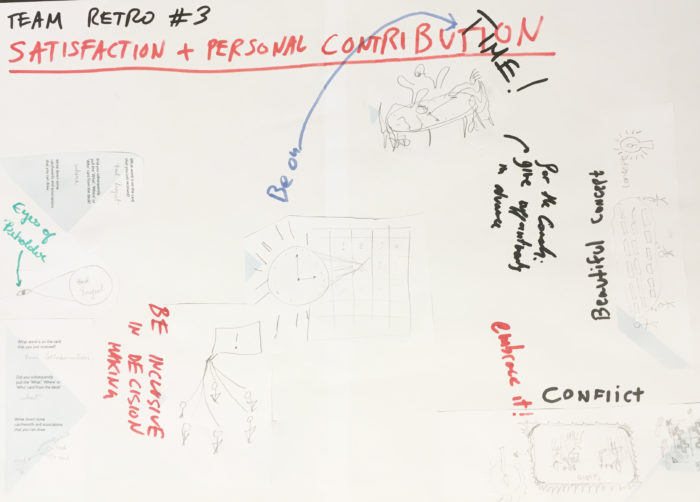

Final visualisation

At the end of the ‘game’, the students did another visualization of their findings and conclusions. Similar to the project WEB session, it turned out they needed more guidance to complete this final stage. When I ran this session, I didn’t have the time to develop these guidelines which resulted in a broad and somewhat poorly defined assignment:

The students will present the issues they discussed during the course of the game in a visual way, using the drawings they made in combination with the A3 sheet of paper. This will take no longer than 15 minutes.

At first, the students didn’t feel the urge to summarize that which had been discussed, or to draw conclusion from it. They merely focused on their own drawings and started cutting them out without consulting with their fellow students. The coach, originally a graphic designer, intervened and urged the students to discuss which drawings to select. “How can we do this? Can we formulate some wishes or rules for the next sprint?” Looking at the drawings, he concluded that the session’s main themes had been “satisfaction, personal contribution and desires that are accounted for”. He stated that the following rules would make for a better collaboration:

- Be on time

- Be inclusive in decision making

- Embrace conflict

- Own the project!

Conclusion

A lot went right during this day and a lot went wrong as well. This made for a very eventful session. For the next session, I’ll be focusing on these issues:

- The themes need to be worded more clearly. For example, I’ll have to come up with an alternative to phrases like ‘bad’. Participants sometimes need to specify a broadly worded term, and vice versa. This session involved a coach but in the event a coach is not present, I may be able to appoint a moderator. The moderator would have to adhere to the following diagram:

- I’ll have to rephrase the assignment for the final visualization much more clearly.

The coach made a few very helpful suggestions to the students during the final visualization:

- Write down ‘action points’ that you can use as a new set of rules

- Summarize the conversation, wait a week, then set up a number of rules according to the summarization you made

- View the final visualization as a summary or a journal that documents the conversation.

- Take another person’s drawings and write down your reactions to it.

- I’ll have to figure out how to make the drawings contribute more to the conversations. The coach noted that the allotted time for drawing was too short to allow students to stimulate their ‘lateral thinking*’. The goal of my method isn’t to have students engage in lateral thinking because they’re not participating to arrive at a solution to a problem. That said, I do think the ideas that could stem from lateral thinking may be of value.

In any case, it was clear that the drawings, as an end result, were not contributing enough to the conversation but that the act of drawing in itself is of added value: the participants get into a separate flow through the drawing, they have the time to really contemplate the themes and are encouraged to go in-depth by the Who, What, Where-cards. Aside from that, they put themselves in a vulnerable position by showing their work to the others. This contributes to the magic circle. It’s worth investigating the way drawings and the final visualization could potentially contribute more to the conversation and to summarizing it.

I got the impression that the students were discussing more subjects more openly than they normally would, even if the were occasionally reluctant to contribute and the atmosphere was often tense. A lot of useful point arose from their discussions as well. However, they themselves seemingly failed to see the usefulness of their session. I might have prevented this by calling out certain key points in the session and why they’re important and potentially useful to the participants.

The coach told me afterwards that he thought the method was a good way to spark up a conversation in a new and different way. Like me, he got the impression that the students were mostly contributing just because they felt they had to. He also agreed that the drawings could’ve contributed more.

*Lateral thinking is based on re-arranging of existing information with the purpose of creating new information. A problem usually has a starting point and an end point. The thinking process is finding a way between these two points. Typically, people tend to want to draw a straight line between these points. If an eventuality arises that could disrupt this straight line, people tend to discard the entire potential solution in favor of a brand new one. Lateral thinking encourages one to continue down the chosen path, bearing in mind the possibility that their solution could potentially be the right one after all. This allows for people to see beyond their apparently impossible situations and leads to new insights.